Ancient Times

Since antiquity, people have tried to understand the behavior of matter: why unsupported objects drop to the ground, why different materials have different properties, and so forth. Another mystery was the character of the universe, such as the form of the Earth and the behavior of celestial objects such as the Sun and the Moon. Several theories were proposed, the majority of which were disproved. These theories were largely couched in philosophical terms, and never verified by systematic experimental testing as is popular today. On the other hand, the commonly accepted works of Ptolemy and Aristotle are not always found to match everyday observations. There were exceptions and there are anachronisms: for example, Indian philosophers and astronomers gave many correct descriptions in atomism and astronomy, and the Greek thinker Archimedes derived many correct quantitative descriptions of mechanics and hydrostatics.

Middle Ages

The willingness to question previously held truths and search for new answers eventually resulted in a period of major scientific advancements, now known as the Scientific Revolution of the late 17th century. The precursors to the scientific revolution can be traced back to the important developments made in India and Persia, including the elliptical model of planetary orbits based on the heliocentric solar system of gravitation developed by Indian mathematician-astronomer Aryabhata; the basic ideas of atomic theory developed by Hindu and Jaina philosophers; the theory of light being equivalent to energy particles developed by the Indian Buddhist scholars Dignāga and Dharmakirti; the optical theory of light developed by Arab scientist Alhazen; the Astrolabe invented by the Persian Mohammad al-Fazari; and the significant flaws in the Ptolemaic system pointed out by Persian scientist Nasir al-Din al-Tusi. As the influence of the Islamic Caliphate expanded to Europe, the works of Aristotle preserved by the Arabs, and the works of the Indians and Persians, became known in Europe by the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Middle Ages saw the emergence of experimental physics with the development of an early scientific method emphasizing the role of experimentation and mathematics. Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965-1039) is considered a central figure in this shift in physics from a philosophical activity to an experimental one. In his Book of Optics (1021), he developed an early scientific method in order to prove the intromission theory of vision and discredit the emission theory of vision previously supported by Euclid and Ptolemy. His most famous experiments involve his development and use of the camera obscura in order to test several hypotheses on light, such as light travelling in straight lines and whether different lights can mix in the air. This experimental tradition in optics established by Ibn al-Haytham continued among his successors in both the Islamic world, with the likes of Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī and Taqi al-Din, and in Europe, with the likes of Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, Witelo, John Pecham, Theodoric of Freiberg, Johannes Kepler, Willebrord Snellius, René Descartes and Christiaan Huygens.

The Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution is held by most historians (e.g., Howard Margolis) to have begun in 1543, when the first printed copy of Nicolaus Copernicus's De Revolutionibus (most of which had been written years prior but whose publication had been delayed) was brought from Nuremberg to the astronomer who died soon after receiving the copy.

Further significant advances were made over the following century by Galileo Galilei, Christiaan Huygens, Johannes Kepler, and Blaise Pascal. During the early 17th century, Galileo pioneered the use of experimentation to validate physical theories, which is the key idea in modern scientific method. Galileo formulated and successfully tested several results in dynamics, in particular the Law of Inertia. In 1687, Newton published the Principia, detailing two comprehensive and successful physical theories: Newton's laws of motion, from which arise classical mechanics; and Newton's Law of Gravitation, which describes the fundamental force of gravity. Both theories agreed well with experiment. The Principia also included several theories in fluid dynamics. Classical mechanics was re-formulated and extended by Leonhard Euler, French mathematician Joseph-Louis Comte de Lagrange, Irish mathematical physicist William Rowan Hamilton, and others, who produced new results in mathematical physics. The law of universal gravitation initiated the field of astrophysics, which describes astronomical phenomena using physical theories.

After Newton defined classical mechanics, the next great field of inquiry within physics was the nature of electricity. Observations in the 17th and 18th century by scientists such as Robert Boyle, Stephen Gray, and Benjamin Franklin created a foundation for later work. These observations also established our basic understanding of electrical charge and current.

In 1821, the English physicist and chemist Michael Faraday integrated the study of magnetism with the study of electricity. This was done by demonstrating that a moving magnet induced an electric current in a conductor. Faraday also formulated a physical conception of electromagnetic fields. James Clerk Maxwell built upon this conception, in 1864, with an interlinked set of 20 equations that explained the interactions between electric and magnetic fields. These 20 equations were later reduced, using vector calculus, to a set of four equations by Oliver Heaviside.

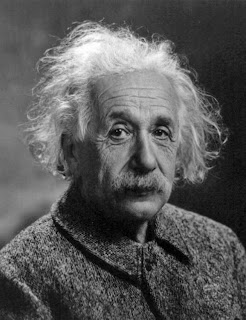

In addition to other electromagnetic phenomena, Maxwell's equations also can be used to describe light. Confirmation of this observation was made with the 1888 discovery of radio by Heinrich Hertz and in 1895 when Wilhelm Roentgen detected X rays. The ability to describe light in electromagnetic terms helped serve as a springboard for Albert Einstein's publication of the theory of special relativity in 1905. This theory combined classical mechanics with Maxwell's equations. The theory of special relativity unifies space and time into a single entity, spacetime. Relativity prescribes a different transformation between reference frames than classical mechanics; this necessitated the development of relativistic mechanics as a replacement for classical mechanics. In the regime of low (relative) velocities, the two theories agree. Einstein built further on the special theory by including gravity into his calculations, and published his theory of general relativity in 1915.

One part of the theory of general relativity is Einstein's field equation. This describes how the stress-energy tensor creates curvature of spacetime and forms the basis of general relativity. Further work on Einstein's field equation produced results which predicted the Big Bang, black holes, and the expanding universe. Einstein believed in a static universe and tried (and failed) to fix his equation to allow for this. However, by 1929 Edwin Hubble's astronomical observations suggested that the universe is expanding. Thus, the universe must have been smaller and therefore hotter in the past. In 1933 Karl Jansky at Bell Labs discovered the radio emission from the Milky Way, and thereby initiated the science of radio astronomy. By the 1940s, researchers like George Gamow proposed the Big Bang theory, evidence for which was discovered in 1964; Enrico Fermi and Fred Hoyle were among the doubters in the 1940s and 1950s. Hoyle had dubbed Gamow's theory the Big Bang in order to debunk it. Today, it is one of the principal results of cosmology.

From the late 17th century onwards, thermodynamics was developed by physicist and chemist Boyle, Young, and many others. In 1733, Bernoulli used statistical arguments with classical mechanics to derive thermodynamic results, initiating the field of statistical mechanics. In 1798, Thompson demonstrated the conversion of mechanical work into heat, and in 1847 Joule stated the law of conservation of energy, in the form of heat as well as mechanical energy. Ludwig Boltzmann, in the 19th century, is responsible for the modern form of statistical mechanics.

From : www.wikipedia.org

Entangled Ions Measure Time Faster

1 day ago

No comments:

Post a Comment